Challenging Caste Discrimination From Within Caste Associations

Caste associations arose in the late nineteenth century as communities scrambled to define or elevate their social rank during the colonial censuses. Each decade’s enumeration triggered petitions, mythic genealogies and conferences defending or improving a caste’s status. By the 1920s, caste associations meetings had become regular fixtures across the Madras Presidency. Periyar grasped their potential: forums born of hierarchy could be turned into platforms for equality. Addressing them, he began with praise, urged solidarity, and then dismantled the very religious and moral codes that sustained caste. His engagement was a brilliant tactical inversion—using caste organisations to preach caste annihilation and self-respect, and to expose how Brahminical religion underwrote social tyranny.

The Sengunthar caste was traditionally seen as a textile-working community. This speech was delivered at the Coimbatore district conference of Sengunthars on 27–28 December 1925. It was published in Kudi Arasu on 10 January 1926. Towards the end of this short address, Periyar stresses the central tenet of his ideology, a revolutionary message in a caste-bound society:

‘No one is above, and likewise, no one is below.’

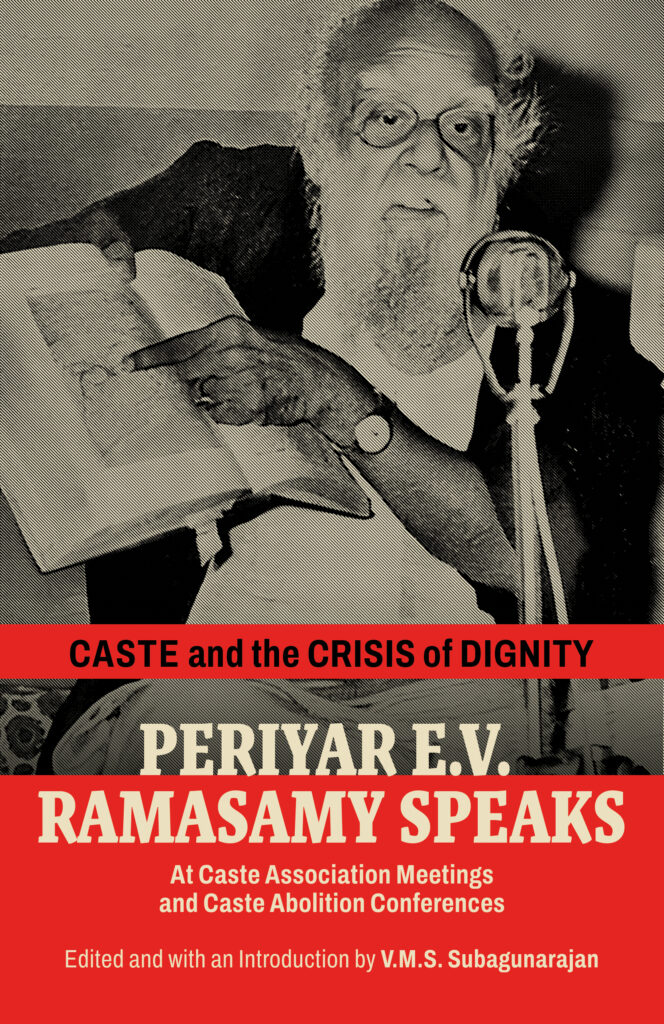

(Excerpted from Caste and the Crisis of Dignity: Periyar E.V. Ramasamy Speaks: At Caste Association Meetings and Caste Abolition Conferences.)

<<<>>><<<>>><<<>>>

Speech at the Coimbatore District Sengunthar Conference

In our country, the Sengunthar community has been living with due pride and influence. Although we cannot deny that it has the ignominy of allowing women to be dedicated to temples as dasis, it has gone through considerable reform since it formed the Sengunthar Sangam ten years ago. No other caste organisation has ensured such progress of its caste. The Sengunthar Sangam has been able to reach this stage because of the sincere efforts of leaders devoted to the community.

But this is not enough. Some shortcomings of the men among this community also need to be set right. Some of them, who have been playing drums [melam] as their source of livelihood, are looked down upon. Because of their profession, these men degrade themselves, consider themselves inferior to others and slouch and crouch in front of other musicians; they think it is their caste dharma to genuflect like Hanuman whenever they see a nadaswara exponent who charges Rs 100 for an hour of concert or even a worthless musical illiterate in sabhas.

In Devakottai, a nadaswaram player [from the Sengunthar community], who was contracted for a concert for a fee of Rs 350, was told by the local people that he could not start his performance if he did not remove his shoulder towel which, incidentally, he wore to wipe off the sweat while playing the instrument. If a vidhwan [maestro] who was given Rs 350 and a second-class train ticket to travel to Devakottai was disallowed to perform with his shoulder towel on, we can imagine how much those ‘lords’ [rich patrons] respect music. So, they should give up that profession and take it up again when it gains respect.

Even now our people are not rational. For instance, whether a Brahmin plays the role of an accompanist, or plays the harmonium or recites Bharatanatyam songs sitting behind a dancing dasi, or acts as a procurer of a partner for her, they address him as ‘swami’; when he brings a letter of ‘procurement’, they stand up and receive it. So, it is better to earn a living by breaking stones or sweeping the streets than being a vidhwan or a drum player before such people.

Even otherwise, we should be men enough to avoid feeling inferior and worshipping anyone. It is a great shame to think that castes such as the Brahmins are superior to us. The ideas that our sins will vanish, that our parents will go to heaven and that we will get good progeny if we share the bed with them harm our self-respect and lead to the slave mentality that tells us we are inferior to them. If we truly believe that no one could ever be below us, then we’ll realise that there is no one above us either. We are made to feel that those who help us in various ways, those who do good to us, those who make it possible for us to breathe clean air are inferior to us because of their karma; at the same time, we are made to feel that dishonest, lowly people who live by sucking our blood are superior to us and that we should worship them, as a means to attain ‘moksha’. I think we can achieve equality and progress only when such problems are removed.

Buy your copy:

https://speakingtigerbooks.com/product/caste-and-the-crisis-of-dignity-periyar-e-v-ramasamy-speaks/