Excerpt: Why India Is a Democracy

Late nineteenth and early-twentieth-century India saw the emergence of a public sphere that enabled magnificent public oratory. Soon, the public articulation of the social and economic problems that afflicted us became the primary vehicle for resistance to the British Raj. But this resistance did not aim merely at removing the colonial power. It was in fact an intense intellectual and political struggle to forge a new unity along a modern entity called India which upheld the civil and human rights of its people.

The following excerpt, from the editor Rakesh Batabyal’s introduction to Building a Free India: Defining Speeches of Our Independence Movement that Shaped the Nation, brilliantly highlights this aspect of our freedom struggle.

Two fundamental characteristics emerge from reading hundreds of speeches people delivered during the freedom movement in different parts of the country. First, a ceaseless endeavour from the beginning to humanize the state in India. Second, a sustained effort to ennoble the people of the landmass; nationalism was found to be the vehicle to achieve this ennobling process.

… It was by investigating the logic of colonialism and attempting to understand why—despite all that they could see as good in the colonial presence—nothing explained the poverty and famines and sickness that pervaded the land, and for which none took responsibility, that [the early nationalists] came to recognize colonialism’s dehumanizing character. Since the British were the overlords, they could see that it was the responsibility of the British. The critique, presented in the early years particularly to a British audience, was thus always motivated by a desire for a more just and more humane system to be brought about in India, a promise which the British themselves had made.

Equally significantly, the speeches, whether made within the precincts of the legislative assemblies or in the sessions of the Indian National Congress or in courts of law, desired the evolution of a sense of an Indian state. The state they began to conceive was a state that could harmoniously blend the best of the democratic model with the developing understanding of civil rights, the rights of minorities and a notion of universal brotherhood. That there was a sustained critique of the colonial government’s attitude to curb civil rights at the drop of a hat can be seen from the days of the Ilbert Bill protest in the early 1880s. It was through the sustained attack by the brilliant Surendranath Banerjee, Vithalbhai Patel, Mohammed Ali Jinnah and Madan Mohan Malaviya among others that one saw the complete delegitimization of the effort of the colonial government to pass the Rowlatt Act in 1918–19.

Similarly, a decade later, by which time many significant events had taken place, including the Gandhi-led movement for non-cooperation, it was the consolidated attack, led this time by the chairman of the Assembly, Vithalbhai Patel himself, on the Public Safety Act of 1928 that dampened the official enthusiasm in passing the abhorrent law. In this regard, the often sarcastic remarks of Tanguturi Prakasam, the great Indian jurist, in the Assembly, protesting on behalf of putative communists whose civil rights could be taken away under the provisions of the Bill, despite the differences he may have had with the communists, is further testament to the enlightened and free society the leadership envisioned. The brilliance of many such speakers across the country gives us the sense that Indians, when they were under a colonial empire, fought against efforts to take away their liberties better than they did later when they were free and had their own government!

The efforts at humanizing and ennoblement received a fresh moment with the beginning of the movement of Gandhi.… [T]he nature of speeches of both Gandhi and the entire generation of leaders, public speakers or intellectuals, took at this stage a different turn. They were no longer steeped in parliamentary language but spoke in terms of transformation: transformation of the world we all live in and how we look at it. They wanted to transform society and end the colonial state as soon as possible. This urgency was also associated with the intensification of the radical social and political movements across the world and more so the world with which India was connected.…

Change of the style and content was best manifested in the Karachi Resolution of the Congress which spoke of fundamental changes in Indian society and also about the need for fundamental rights to be enshrined in any form of constitutional provision the future would bring.…

One significant aspect of this period, as noted above, was also the gradual insignificance of parliamentary discussion as the tallest among the leadership were outside legislative politics and were engaged with the nation-making and movement-related work. Gandhiji himself was engaged in what he termed as constructive works.…

The speeches outside, therefore, now set the social and political agenda. It is here that the national movement was lucky to have one of the finest speakers of the time in Jawaharlal Nehru. Nehru’s presence itself was electric. Subhas Chandra Bose introduced a distinct charm with a combination of emotion and discipline and was a magnet to the youthful audiences of the 1930s and ’40s. Not only did they radicalize the youth but also familiarized them with the global trends in the movement of the youth and the socialist turn across the world.… The 1929 Lahore session of the Congress therefore heralded a paradigm shift where nothing short of independence became the political goal. This 1930s radicalization also saw the emergence of political organs of the communists, socialists and Depressed Class parties, bringing many new leaders to the fore. The amount of proscribed literature of this period also increased. The idea of the nation now embraced ideas of social transformation, where changing the social and economic life of people defined the idea of freedom. Colonialism was now no longer simply foreign rule but also the biggest impediment to carrying out that transformative act.

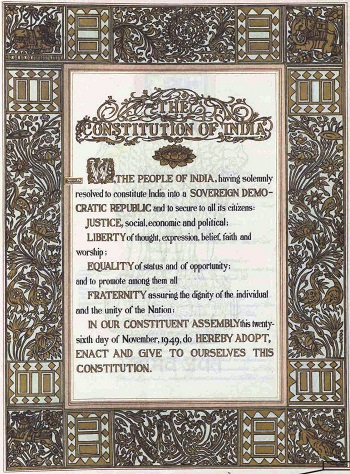

It is in this background that Independence and the Constituent Assembly debates brought back the importance of the public articulation of governing principles and policy inside the legislature.… Speakers who were hitherto engaged in changing the world outside were brought inside. The struggle to humanize the state and ennoble the people now needed to be enshrined in a constitution that would guide the independent nation.

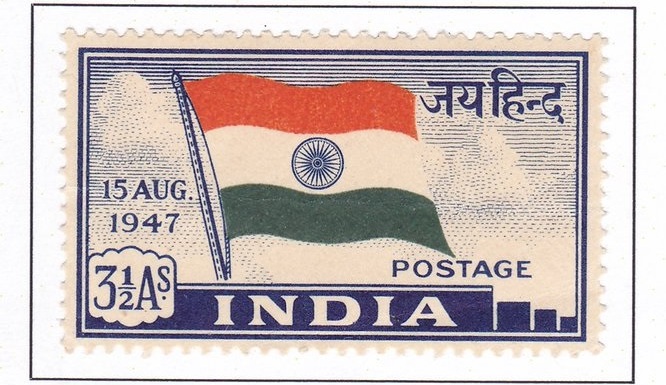

The Constituent Assembly, while reflecting all that was best in the struggle, still needed attempts to see the unfathomable future that lay ahead. Thus, on the one hand, the idea of the national flag condensed the ideas of the freedom struggle in the form of a symbol, and on the other, the objective resolution gave us what they thought ought to be the guiding vision of the new society. The Constitution therefore, in a sense, embodied the history of the freedom movement, and simultaneously became an inalienable part of this history. The ideals of a secular, democratic and just order were not merely the creation of the Assembly but the product of the movement itself.

Featured image: First stamp of independent India with the Tricolour on it.