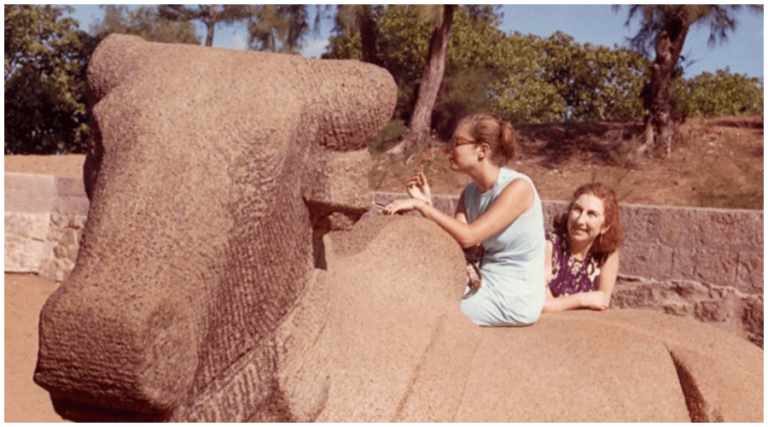

Excerpt: An American Girl in India

In the early 1960s, a twenty-two-year-old, who would grow up to become an authority on Hinduism and world mythology, visited India for the first time. Over the course of her year-long stay she wrote a series of letters to her parents about her experiences. Related through these letters and her recollections, An American Girl in India is an enchanting profile of both the young woman and the young nation.

Trying to cram every last detail into each letter, young Wendy Doniger describes, in this letter dated September 15, 1963, everything she did in the last four days—the beginning of autumn, visits to Bolpur, and the mechanics of a temple ritual she doesn’t fully understand.

September 15, 1963,

Shantiniketan

Now autumn has begun to set in. Everywhere the fields are filled with kash, which is a kind of feathery white flower, shaped like wheat, but made of the fuzzy stuff that flies in the air when dandelions go to seed, but silkier. Kash is to autumn here what the turning of leaves is to autumn there. It still rains every day, but only for a short time, and the ground is dry again in an hour, though the sun is not very hot. I went to Bolpur to buy some saris and a round of sulfaguanidine and enterovioform for the boys in the back room [a line from an old Marlene Dietrich song], and it was market day. The road was filled with pregnant goats and tiny fuzzy calves and sadhus looking very saintly and beautiful in their long white hair and beards. Near a store there was a woman crouching on the ground, crying in a weeping, rhythmic way, and there was a circle of children around her. I found out that the man in the shop said that she had tried to steal rice, and he had beaten her. She said that she had paid him, but she didn’t say it with much conviction. We bought some rice and put it in her bowl, but she kept on moaning softly. Usually I am afraid to give money to the beggars; I can’t explain why. They chant from a distance, and the sound gets closer and closer, and takes on a remote resemblance to the religious chant it is supposed to be, and then you hear the footsteps, and suddenly you see a face right at your window, a thin, scarred, discoloured face with wrinkles that are almost like folds, and a hand is thrust in between the wrought iron latticework of the window, and the voice is as rhythmic and whining as the sound a chicken makes. The first time anyone came to my window I actually ran away; now I give once a week to quiet my conscience a little, and then whenever I hear that droning sound, I take my book and go to a room that has no outside window, and I hear the sound coming to my window, and waiting there, and then it goes away, and I return to my desk. This happens perhaps twice a day.

Well, we went on to Bolpur. The huts there are covered with thatch, and on the walls there are hundreds of neat round paddies of cow dung, which they put on the walls to dry and then use for fuel. (My food is all cooked over cow dung, and it all tastes like cow dung to me. I know it’s all in my mind, but it really does taste sort of smoked, especially the bland foods, and not smoked with just anything.) It used to give me quite a start to see a little girl of three or four, carrying a little bowl under her arm, suddenly run to pick something up, and I would think she had found a stone or a plant or something, and then she would stoop and eagerly put her hand into a great wet cow flop, and scoop up several handfuls and put them into her bowl with great gusto, and then go on looking for more. Then she would make it into mud pies and paste it on the sides of the house to dry. I’ve gotten used to seeing it now, but it does spoil my appetite for an hour or two.

On the side of one of these clay, thatched huts I saw a bas relief of a horse, in stature and stance somewhat resembling the T’ang horses at gallop, and in style something like the Picasso bulls, altogether one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen, and about eight feet long. I keep meaning to take a photograph of it, but I never carry my camera here because it’s home to me. Sometimes I see little white boys, but completely white, albinos with white hair and skin, playing with the Santhals, who are very dark, but they are purely hereditary accidents; there is almost no intermarriage with white-skinned people among the Santhals.

It is difficult to shop in Bolpur, because the stores open for half an hour, then close for two hours, then open for fifteen minutes, then close again, and so on, and as each shop has its own schedule, and as no one has a watch anyway, and as store hours (as well as the hours of classes at Shantiniketan, by the way) change every week or so as the hours of sunlight change, it is very confusing. Moreover, the store closes when anyone dies, and as someone is always dead, it is hard to find a time when you can buy several different things. Things at Shantiniketan are casual, too. Yesterday it looked like a fine day (here a fine day is a cloudy day; a clear day, the kind that we would call fine, is too hot to be fine) and so the students went to the vice chancellor and asked for a holiday, and he agreed, and so everyone went on a five-mile hike to the river, and pushed each other in, and then came back, getting thoroughly drenched by the rain on the way, and had afternoon classes. It’s called an ‘outing’, and the students are allowed ten per year, whenever they want. The teachers come too, or else they go home and have tea.

I have not yet begun my Sanskrit classes, because my professor was supposed to arrive last week, but last week was the dark half of an inauspicious month, so he has to wait until the end of next week to come here, and meanwhile I am doing my research by myself, and getting along very well, inauspicious month or no. (I am temporarily studying with another pandit.)

I was asking about the winter here, trying to find out if I needed more warm clothes, and nobody seemed able to tell me how cold it would get. Finally, Chanchal said, ‘You know, Wendy, to tell the truth, after living through the heat each year I always forget what the winter is like.’

I have had to give up eating mangoes (though I love them dearly and was accustomed to having several at every meal), because they aren’t good during the monsoon (like oysters in ‘r-less’ months) and they make you sick. They made me sick, but it was worth it, and now I am all better.

I went to a Hindu temple service in the village here. At the appointed time everyone (about ten people) rings a bell or bangs on a brass bowl or blows on a conch shell (which sounds like the shofer or chauffeur or however you spell it that you blow on Yom Kippur), and generally makes a terrible racket for about five minutes, during which the lizards all come out to see what’s up, and the children run around and are slapped by their mothers, and the sadhus go on chanting, looking up angrily now and then to quiet the children (though how the noise can make any difference in that terrible bedlam is more than I could see; I think they just want to see if anyone is watching them chant), and then the priest of the temple throws a lot of water and flowers at the statues of the gods (a combination of Vishnu, Kali, and the Bengali snake goddess, enough to warm the heart of any ethical culturist, or Unitarian, or syncretist in the neighbourhood) and then throws some more at the people, and then he sets down a flaming incense burner, and everyone runs their fingers through it the way we used to dare each other to do with a candle flame, and then they sort of wash their faces with the smoke, or make the gesture of doing so, and the priest chants in a monotone exactly like Cardinal Cushing [Archbishop of Boston], so that all you can make out is an occasional ‘with thee’ or ‘Jesus’ (in their Bengali equivalents, of course), and then suddenly the noise stops, and everyone throws himself down on his hands and knees and face, and the priest sprinkles them, and it is all over. Then everyone is given a kind of candy made of milk, which is very sacred; the Bengalis say it is god, but I think they just like an excuse for candy (they eat it all the time, and are famous for their sweet teeth).

Then we drove home, smelling the particular smell of India that is compounded of incense, sweat, flowers, dust, cow dung, sour milk, melted butter, rain, grass, and wet earth. When I got home I took a new cake of soap, and it was from the Montauk Manor, and never was any piece of soap so incongruous; as I looked at it I thought of, and felt, the posh dining rooms, and the big bathrooms, and the hot water, and the band music, and as India was so strong around me, I really felt very strange indeed. …

Featured image: Wendy Doniger with her mother, Rita, in Mahabalipuram, 1964.