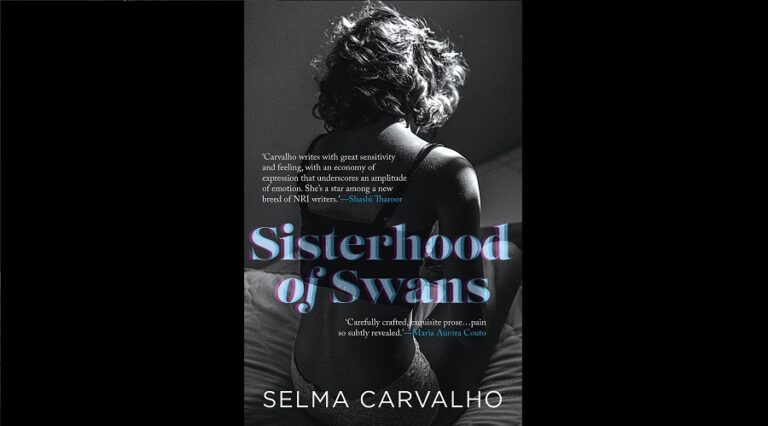

Excerpt: Sisterhood of Swans

The subtle eroticism and exquisite prose of Selma Carvalho’s Sisterhood of Swans sweep you into the world of Anna Marie Souza, a second-generation British-Indian immigrant, whose chaotic childhood and broken home create in her an indefinable sense of yearning that propels her into a series of doomed relationships. Here’s an excerpt from the novel:

The summer I turn fifteen, Daddy moves out. I don’t understand why he is abandoning me. I tug at his shirt and wrap my arms around him, but he leaves anyway.

Months later, he invites me to spend the weekend at his new home. He’s living on the other side of Horton, a small village on the hem of north London. My parents have only ever known Horton as their home in Britain. Mummy was already pregnant with me, when they landed at Heathrow Airport on a cold December day in 1989; two Goans looking for a new life. Horton lies not far from Heathrow. Horton blurs the boundary between London and the great expanse of the country that exists outside of it. In the summer, cob horses graze on the open field which backs on to Otterfield Lane. It’s hard to imagine otters this far out from deep river, but they must have come up the sleeve of the marshy bank at one time, because places and families carry names that mean something even when everything else alters course.

When I arrive, Daddy’s standing in front of a stump of a house springing forth from feathering tufts of grass, enclosed in a pale blue fence with its serrated mouth bleeding berries. He draws me into a circle of arms. I am even further away from him than I was when he lived with us. He is a stranger; a soft-bellied, smiling stranger. The type you meet in corner-shops.

His new love-interest comes out to meet me.

‘This is Martha,’ he says, pulling her close to him.

She’s wearing the taut smile she must have worked on for a week. She’s a thin English woman with coarse hair. This doesn’t look like something Daddy has fallen into arse-backwards. This has the whiff of careful planning, and Daddy’s protective hand on her swollen belly confirms that. We are all connected now by an invisible wire which passes from my ankle through to Daddy’s heart and into Martha’s belly. But Daddy is severed from Mummy. I feel a metal cutter clipping away at the wiring holding us all together.

I trail my trolley bag into the house. Inside, the house is violent with noise from the TV. There’s a boy of about seventeen sitting on the sofa in the small living room crowded with mismatched furniture. It occurs to me that this isn’t Daddy’s home at all. That he’s in fact living in Martha’s home.

The boy looks so much like Martha that he can only be Martha’s son. He’s all dangly arms and legs. I look at him more closely. He’s quite beautiful with a long, oval face unscarred by puberty. Whatever little hair had shown up on his face by way of a beard and moustache has been shaved off, leaving behind stubble which makes him look almost manly. I see a large Adam’s apple bobbing on his scrawny neck. His eyes are fixed on the TV, his hands are manoeuvring a retro joystick. Occasionally, triumph registers on his face.

Daddy plops himself on the sofa, next to the boy.

‘Daniel, this is my daughter Anna-Marie,’ he says.

Daniel nods in the direction of the TV, unwilling to break gaze. There’s a victory achieved on the lighted screen, which makes him jump up in his seat. He slaps Daddy’s thigh. I notice Daddy inch his leg away. Daniel is trying to negotiate space in my Daddy’s life, just as I am, only Daddy has no place for him. Daniel and I belong to no one. I make a silent promise to myself: I’ll never leave the father of my child. I’ll stay. Whatever it takes, I’ll stay till their tiny arms no longer feel the need to wrap themselves around a father.

~

Later in the day, Daddy is on the sofa, his legs propped up on the armrest, watching football. Daniel is watching the game with him.

‘Shower?’ Daddy asks, seeing me walk towards the bathroom, pink towel and shampoo bottle in hand. I nod.

‘Remember how you used to fight me when I would scrub you?’ He laughs into his beer can.

I stare blankly. Daniel looks at me, a clown-smile painted on his face. I don’t want Daniel to know that the man on the sofa—my father—had scrubbed me. That he had prised open my unwilling hands and legs, and scrubbed off the caked playground mud with a pink scrub.

‘Someone has to take care of you,’ he would say, hauling me into his arms and lowering my body into the tub. He’d kneel by the tub, watching the water turn soapy, then he’d leave me to it.

When I’d told Sujata at school that Daddy bathed me every evening, she’d said, ‘Ew. Why?’

But I wasn’t soured on my Daddy as Sujata was on hers. Sujata, at six, planned to run away from home as soon as she’d saved up a pound.

‘Why can’t your mum do it?’ Sujata had persisted, her tiny teeth biting into an apple. Sujata hated fruit but had to eat her share at carpet-time or Miss Folan would make her sit in the corner. Sujata hated a lot of things: dogs, bees, darkness.

‘She goes out.’

‘Where does she go?’

‘To catch butterflies.’

‘With a net?’

‘I don’t know.?’

‘I wish my Daddy would catch butterflies. But he never goes out.’

I’d felt nothing in those days. Neither shame nor guilt. I’d lain in that bathtub of ceramic pink, naked, shimmering and silken, the rippling water conniving, half-truths raging and rising like so many moons tossed into the sky. I’d gathered all the storms in that house, thundering and striking, bolts of lightning flashing and flaring between Daddy and Mummy, and sunk deeper into the water. But Daddy had always fished me out, towelled me dry, and put me to bed. Our bodies fit into each other perfectly, my little hands curled around his neck, my knees tucked into his belly, my chin nuzzled into his chest. He was big and warm, like a gentle giant, and he made me feel safe.

The next morning, Daniel is sitting at the kitchen table, his fingers nimble on a Nintendo console. I pull back a chair to sit next to him.

‘D’you like Pokémon?’ he asks.

‘No.’

‘Where’d you go to school?’

His eyes are snakes slithering over my breasts. I push my breasts further out. They are almost touching his elbow now.

‘Grover’s Green.’

‘Why so far?’

‘It’s a grammar school.’

‘Upcote’s?’

‘Yah.’

‘Posh then, innit?’

‘Not really. It’s just a school.’

‘Annie tried to get into a grammar. Couldn’t.’

‘Who’s Annie?’

‘Me and Annie hang out.’

My shorts ride up my chicken-skin thighs exposing expanses of flesh. My knuckles are red from clenching the sides of my chair. I want to ask him about things—about football, about bikes, about Gameboy—but my tongue sits thick and heavy in my mouth, wallowing in a pool of self-loathing. Under the table, hidden from view, is a world of half-formed desires. I am no longer Daddy’s little girl.

Daniel licks his rhubarb-red mouth, and stands up. His eyes are cloudy with want. He’s just a boy. Not yet a man. But already he knows that he holds the upper hand. That he’ll always hold the upper hand with women.

‘Will you be back next week?’

He’s standing so close to me now that I can feel his breath on my neck. Under his X-Men T-shirt I discern a cage of antlers. His skin smells of the musk of his species. He’s stronger than he looks. He will grow up to be a fine breeding bull.

I say, ‘I don’t know.’

But I do know.

~

Saturday next, I am on the doorstep of that ugly house yet again. Daddy elbows the door open. We’re going to drop this off at Barnardo’s, he says, holding a box of books. Books he no longer needs in his new life. Books which had been such a big part of his old life. Books, Martha who has slid out of the shadows behind him, has probably never read. He’s out of breath, his stomach bulging over his belt. Make yourself at home. Daniel’s in his room, he says, turning to look at me over his shoulder before he shuts the door.

The house is a monastery of quiet rooms and cold floors. The long shaft of afternoon light leaking from Daniel’s half-closed door beckons me. I knock on its paint-peeling front.

‘Come in,’ Daniel says. ‘You’re back.’

Standing at the foot of the bed, I nod. He’s wearing shorts and a T-shirt, his head propped on a tower of pillows, his blackened knees flexed, his fingers on a console. His legs are scrawnier than I thought they’d be, and I wonder now if I’m ready to see his scrawny body naked. He’s just a boy. A stupid boy. Not yet a man who might be warm, gentle and safe. I sit on the edge of the bed, my eyes on the summer-leafing sheets.

‘Pokémon again?’

‘Um-hm.’

I make to go, but his body has sprung into motion, and leapt right next to where I’m standing. He holds my wrist in a firm grip, hurting me. I don’t understand his need for power; I’m humiliated by it. I squirm. He lets go, leaving a ring of white on my skin. My insides are rattling winds and crackling trees. I’m acutely aware Daniel is different from me. He is what Mummy calls ‘not our type.’ Mummy is a poet. She is forever trying to capture the zeitgeist of her times, her butterflies, she calls them. She’s raised me to be liberal, but Mummy’s mouth is so cruel about Daddy’s new family, that the boundaries of acceptance have blurred within me. The snobbery of class and breeding now raises itself like a forbidding nationalist monument. And yet a warm desire seeps through my pride, spreading to my body. I move awkwardly toward him.

Daniel’s lips curl, his tongue twists, his teeth gird upon my mouth. His hands reach under my blouse and unhook the metal clasp which holds my breasts in lacy half-cups. My breasts pour into his palms. His fingers graze my nipples. I try to focus on the wall behind him. I inhale deeply of the sweat beading on his neck. But it’s no good. I clamp shut my thighs. Inexperienced as I am, I know that my legs should be falling away, that I should be guiding him into my joins and dips. Sujata and I, we’ve talked about this so many times, it should be like answering an exam.

‘Fuck, fuck, fuck. Are you a virgin?’ he yells, as if in pain.

My eyes are tearing up. He pushes himself away. He’s islanded amidst the paisley leaf bedding. He has no interest in being my ‘first.’ We are not friends to patch over this with forgiveness. We are not lovers, to be patient with each other’s failings. We are strangers at a mountain impasse manoeuvring past our inexperience. I hook my bra. He returns to playing Pokémon.

In the morning, Martha is in the kitchen, a steel knife in hand, its butt pressed into her palm, its edge cutting through the pale pink of sinew. She wields the knife with precision, letting the blood bleed onto her hand. The meat is diced methodically until all that remains of the clod is bone. She looks at me as I sit at the table.

‘Where’s Daddy?’ I ask.

‘Out in the garden,’ she says, nodding in the direction of the open window.

My heart is a rock wedged in my throat.

‘And Daniel?’

‘He’s spending the day at Anne’s. Down the road. Best of friends, those two are. Always with each other. Childhood sweethearts, you might call them.’

She knows. Just as every woman knows. We belong to the sisterhood of swans, seeking to pair for life, curving our necks to entwine with the perfect mate. Only we seldom find them. Our species is doomed to disappointment.

Outside sits a granite London sky, penetrated by red roofs. Daddy is hunched over a patch of green. I want to crawl into him, cradle my head in the crook of his arm, fasten myself to his chest. But he’s there, weeding another woman’s back garden and smiling at her from where he’s crouched, ankle-deep in sod.