The Hindu–Mughal Alliance: What the Emperor’s General Reveals About India’s Golden Age

In 1582, Emperor Akbar issued an order to translate the Mahabharata into Persian, titled the Razmnama.† The monumental task of translating the text, which comprises over one lakh (100,000) shlokas (stanzas or verses), was carried out between 1584 and 1586.

It is highly probable that Raja Man Singh was aware of, and closely associated with, the creation of Akbar’s imperial illustrated copy of the Razmnama. He may even have been consulted to comment on the works-in-progress.

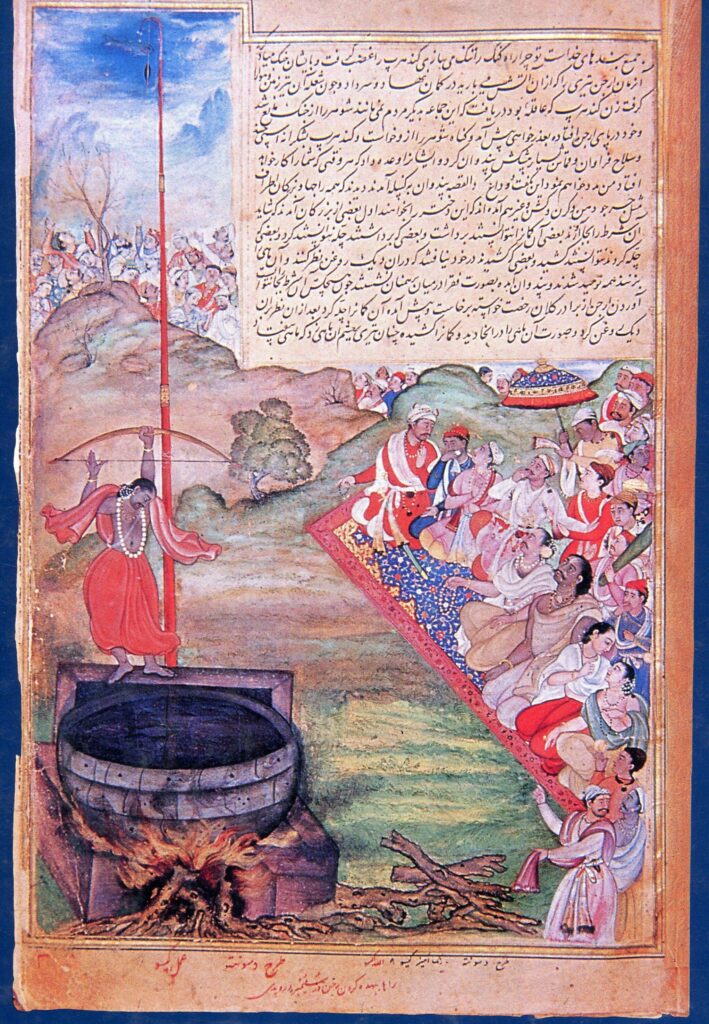

To date, only four illustrated Mughal Razmnama manuscripts are known. One is the City Palace, Jaipur manuscript, which is believed to have been created between 1584 and 1586.* This manuscript eventually came into the possession of Man Singh’s family, although apparently much after his own lifetime, as it bears the seals of Mughal emperors who ascended the throne following his demise. A second copy, believed to have been made between 1598 and 1599, was later split in 1921, with portions now preserved in the British Library, UK, as ‘MS Or. 12076’. The third copy, known as the Birla manuscript, is in the Birla Academy of Art and Culture in Kolkata and is dated 1605. A fourth, from which only two or more miniatures are currently identified, was made around 1616–1617.

Compared with the first copy, the second manuscript contains 161 paintings. These copies were sent as gifts to members of royal families, intended to help them understand Hindu religious texts. According to Akbar’s courtier Abd al-Qadir Badayuni, the emperor ordered that the copies be presented to all the emirs of his kingdom, with instructions to receive them as gifts from God. The preface written by Abu’l Fazl, Akbar’s court historian, notes that the intention behind these gifts and their distribution was deeply pious.

The translation work commanded by Akbar was probably carried out in the emperor’s Maktabkhana, which had been established in 1574. The process for translating Sanskrit works was carefully structured and carried out in several steps. Initially, Hindu scholars (believed to be Deva Misra, Satavadhana, Madhusadana Miara, Caturbhuja and Shaykh Bhavan) explained the meaning of the texts to be translated. Based on these explanations, the Muslim theologian Naqib Khan prepared a first draft in Persian in only one and a half years. This draft was then handed over to the Nagaur-born poet-scholar Faizi,* elder brother of Abu’l Fazl, who converted it into classically elegant Persian prose or verse.

Akbar’s contemporary writer Abdul Qadir Al Badayuni, who was a reluctant and often condemnatory participant in this translation project, described in his Muntakhab ut-Tawarikh that for several nights, Akbar personally explained the text to Naqib Khan, who prepared the initial Persian draft. Badayuni was then summoned to collaborate with Naqib Khan, and in a few months managed to translate two of the eighteen chapters. Other sections were completed by Mulla Shiri and Naqib Khan, while Sultan Haji Thanesari ‘Munfarid’ brought one section to completion. At some point, however, Haji Thanesari was dismissed and sent back to his native city of Bhakkar. Despite that, the work, eventually named the Razmnama (Epic), was fully illustrated and transcribed into multiple copies. Akbar also ordered nobles to have copies transcribed to receive blessings. Abu’l Fazl, the court historian, wrote a substantial preface spanning two quires (juzv) for the completed work.

One of the changes also introduced by Akbar was the official adoption of Persian (Farsi) as the administrative language of the Empire in 1578. By this time, very few nobles of non-Indian origin spoke the older Turki, and in the Deccan, a hybrid language combining Hindavi and Turki had developed. Persian was already in use among the Mughal Court’s elite, and widely used for correspondence, record-keeping, and creative literary writing. Those fluent in Persian were employed at most courts— including that of the Kachhwahas of Dhoondhar—to draft letters and applications for the Imperial Court, as well as to translate communications, and later farmans and nishans, to and from local courts or estates. Its formal adoption for administrative purposes allowed reports from every province—each with its own local languages—to be systematically collected and recorded in the central Record Office of Akbar’s Court.Extracted from The Emperor’s General: The Life and Times of Raja Man Singh of Amber by Rima Hooja.

[Photo: Wikimedia Commons]